Prof. Luisa Klotz and Marie Liebmann analysed the immune metabolism of cells. (Photo: Anna-Lena Börsch)

Muenster – One person can eat large amounts of pasta and still be a small dress size while another looks at a piece of chocolate and puts on weight: metabolism varies between individuals – and this goes beyond a subjective feeling. What is apparent in the overall organism also applies to each cell: the metabolism of individual cell types differs. It is not surprising that in recent years metabolic immune cell disorders have been observed in connection with several autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis. Now scientists of the transregional collaborative research centre (CRC) 128 have demonstrated: the effectiveness of one particular multiple sclerosis drug is due to its direct interference with cell metabolism. And this is only part of the story: the active ingredient under investigation, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), has a variable effect – depending on how the cells of individual patients metabolize it.

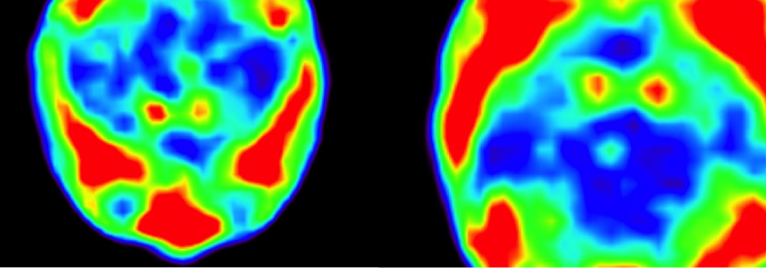

DMF is an approved substance for therapy of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) and reduces the excessive immune reactions in the body. It is known to induce cell death (apoptosis) in immune cells that trigger excessive responses. “It was clear to us that cell death occurs as a result of this drug, but we did not know how,” says Marie Liebmann, a research associate in Prof. Luisa Klotz’s group at the University Hospital for Neurology in Münster. Now it has been proven: The drug specifically targets cells that convert a high amount of energy and thus produce a lot of oxygen. Through a reaction, it leads to even more oxygen being produced, which accumulates in the mitochondria, the powerplants of the cell. This oxygen, however, is highly reactive, putting the cells under high oxidative stress, which eventually kickstarts apoptosis. This type of stress, and even cell death, is to a certain extent desired by nature to enable cell activation.

The mechanism becomes problematic only when it does not happen to the desired extent. In patients with average immune metabolism, just enough cells are killed to maintain a normal immune response. In patients with low cell metabolism, there is the risk of too many T cells dying: leaving immune defenses weakened and infections becoming more likely. This so-called lymphopenia – a drop in T cell count – is a known side effect of DMF and many other drugs used to treat autoimmunity. If the cell counts drop below a certain threshold, therapy must be interrupted as the risk of infection becomes too high. In most cases, the excessive immune response plus inflammation and symptoms of the autoimmune disease will then return.

The latest research from the Münster team – made possible in part by support from the CRC 128 and the Competence Network Multiple Sclerosis – could aid better risk assessment: “We can determine patients’ cell metabolism on an individual level and thus check whether this side effect is likely,” Prof. Klotz explains, who works as a senior physician in the Department of Neurology. “But this is just the beginning,” she says since DMF is not the only drug that works differently in different patients. Already some time ago, Prof. Klotz’s team could prove similar mechanisms underlying multiple sclerosis therapy with the active ingredient teriflunomide. “It is certainly worthwhile to identify cell metabolism types in multiple sclerosis patients to be able to offer individual patient-level treatment,” Prof. Klotz adds looking towards future needs.

Reference:

Liebmann M, Korn L, Janoschka C, Albrecht S, Lauks S, Herrmann AM, Schulte-Mecklenbeck A, Schwab N, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Eveslage M, Wildemann B, Luessi F, Schmidt S, Diebold M, Bittner S, Gross CC, Kovac S, Zipp F, Derfuss T, Kuhlmann T, König S, Meuth SG, Wiendl H, Klotz L. 2021. Dimethyl fumarate treatment restrains the antioxidative capacity of T cells to control autoimmunity. Brain. 144(10):3126-3141.